Textual Analysis of "J’ay perdu ma tourterelle"

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 This poem, then, seems worthy of a long-overdue examination on its own terms. The first task is to establish an authoritative text. The only scholarly edition of the works of Passerat is Prosper Blanchemain’s 1880 Les poésies françaises de Jean Passerat; this work reprints the first extant text of “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” exactly, only altering “ß” to “ƒƒ” (a double long “s”). All other works quoting or reprinting the poem modernize the spelling and punctuation in widely different fashions, evidently without reference to Blanchemain’s edition. Many textual variants are thus introduced. (See Appendix III for a full collation of twenty-eight texts, no two of which are the same, and a transcription of the first printed text with unmodernized characters). My own conviction is that for early modern texts where there is little or nothing to impede contemporary comprehension of the original, the spelling, punctuation, and lineation of the first manuscript or printing ought to be retained. As I argue below, modernizing this particular text erases one of its more interesting poetic devices.

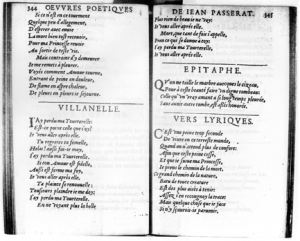

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 I give here the text of the first published version, that of 1606. The type of that version is italic, which I have not retained; unlike Blanchemain, I have also modernized “i” to “j”; “ƒ” (long “s”) to “s”; “u” to “v”; and “ß” to “ss” according to standard practice. Otherwise, I have been careful to retain the spelling of the original, as well as its punctuation and lineation. See Figure 1 for a page image of the source text; I also include below an English prose translation of the poem that appeared in Geoffrey Brereton’s 1958 Penguin Book of French Verse:

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 VILLANELLE.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle:

Est-ce point celle que j’oy?

Je veus aller aprés elle.¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Tu regretes ta femelle,

Helas! aussi fai-je moy,

J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle.¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Si ton Amour est fidelle,

Aussi est ferme ma foy,

Je veus aller aprés elle.¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Ta plainte se renouvelle;

Tousjours plaindre je me doy:

J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle.¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 En ne voyant plus la belle

Plus rien de beau je ne voy:

Je veus aller aprés elle.¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Mort, que tant de fois j’appelle,

Pren ce qui se donne à toy:

J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle,

Je veus aller aprés elle. (Recueil 344-5)¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 I have lost my turtle-dove: Is that not she whom I hear? I want to go after her.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 You pine for your mate. So, alas, do I. I have lost my turtle-dove.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 If your love is faithful, so is my faith constant; I want to go after her.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Your grieving is renewed, I must grieve always; I have lost my turtle-dove.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 No longer seeing my fair one, nothing fair can I see; I want to go after her.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Death, on whom I call so often, take what is offered you. I have lost my turtle-dove; I want to go after her. (Brereton 91-2)

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Figure 1: Jean Passerat, Recueil des oeuvres poétiques de Ian Passerat augmenté de plus de la moitié, outre les précédentes impressions (Paris: Morel, 1606) 344-5. Image from a microfilm of a copy in the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Apart from its now-familiar formal scheme, the most striking characteristic of “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle”–even to modern eyes and ears–is its plain style. The syntax is generally straightforward, the sentences are brief and declarative, the vocabulary is not Latinate, and there are no classical allusions in the poem–even though Passerat was one of the most reputable classical scholars of the sixteenth century. Passerat was in fact generally out of step with the French poets of his time in this regard; to Passerat’s more famous poetic contemporaries in the Pléiade (Ronsard, Du Bellay, et al.), a poem such as “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” would have looked both slightly dated and excessively ordinary. Indeed, more than one critic has remarked that Passerat’s style in this and other poems is reminiscent of Clément Marot (1496-1544), the chief poet of the previous generation, whose colloquial works fell out of favor with the learned ornamentarians of the Pléiade.1 Passerat admired simplicity.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Another interesting feature of the poem is its conspicuous etymological doubling. Once the mourning dove is likened to the mourning lover in the second tercet with the phrase “aussi fai-je moy” (“so do I”), each of the following tercets introduces an etymologically linked word pair that reinforces the comparison: “fidelle” / “foy” (“faithful” / “faith”); “plainte” / “plaindre” (“complaint” / “complain”); “belle” / “beau” (“beauty” [feminine] / “beauty” [masculine]). These pairs serve to link the first and second lines in each tercet, creating almost the effect of a couplet. Similar wordplay is common in Passerat’s lyrics, as for instance in this sestet of a sonnet in the Tombeau:

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Faites dorenavant que les lis argentés,

Lis honneur des François sur ma tombe plantés,

Le plus bel ornement de la terre fleurie,

Portent à tout jamais marque de ma douleur;

Et les voyant tachés d’une noire couleur,

Qu’on y lise mon nom & celuy de Fleurie. (Recueil 327)¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 See to it henceforth that the silvered lilies

(Lilies, honor of the French, planted on my grave,

The loveliest ornament of the flowered earth)

Bear for all eternity the mark of my grief;

And seeing them smudged with an inky hue,

The world will read my name and that of Fleurie.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 The double chime of “fleurie” (“flowered”) and “Fleurie” (the name given to “Niré’s” mistress) has of course been arranged by Passerat to serve as a key feature of the whole sequence, but chimes such as “lis” (“lilies”) and “lise” (“read”) are unique to each particular lyric. In this sonnet, the “lis/lise” pairing drives the whole poem; the central trope of “reading the lilies” is a semantic device derived from the arbitrary resemblance of the two words. In “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle,” similarly, the central (more subtle) trope–which might be described as doubling, repetition, circularity, mirroring, pairing, coupling, dual identity, infinite regress, semblance, resemblance–draws semantic power from the likeness of signs.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Another doubling effect of “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” (and of Passerat’s other lyrics) is strictly visual–an effect that can certainly seem arbitrary, so much so that modern readers seem to have missed it altogether. There is good reason to believe that Passerat (or his nephew, Jean de Rougevalet, who edited Passerat’s posthumous publications, or possibly a printer) deliberately ensured that all the line-endings within every poem were spelled alike, even when this entailed altering a more or less accepted spelling. The word “fidelle” in line seven, for instance (which rhymes with “Tourterelle,” “femelle,” and other double-“l” words in the poem), is spelled with only one “l” at the beginning of a line of another poem printed only two pages before “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle”: “Fidele Amant qui planta ce Cyprés, / Digne tu fus de meillure adventure” (Recueil 342). This phenomenon occurs elsewhere in the Tombeau as well; the word spelled “trouve” (“find”) in one poem is spelled “treuve” in another when it occurs as a line-ending rhymed with “fleuve”: “S’il n’y trouve plus d’eau ny verdure ny fleurs”; “Autre remede à mon mal ne se treuve. / Revien Charon pour me passer le fleuve” (Recueil 330, 326). Variant spelling of words was of course perfectly common in the sixteenth century, before spellings had been standardized–but the correct modern spellings are “fidèle” and “trouve,” which suggests (though in hindsight) that the line-ending spellings of “fidelle” and “treuve” were then, as they are now, less correct. The line-ending spellings clearly do not vary at random. Even a quick look through Passerat’s Recueil shows a very high incidence of homographia in the rhyme words. The unanimous visual recurrence of “-elle” and “-oy” as line-endings, then, is surely as deliberate a poetic device as their aural recurrence as rhymes. To modernize the spelling of the line-endings, as so many authors and editors do when quoting or reprinting “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle,” is to destroy this visual rhyme.2

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 The double refrain that is so prominent a feature of the nineteen-line villanelle, then, is on the one hand typical of Passerat’s affection for linguistic doubling of all kinds, but it is on the other hand specific to “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle,” in which the lover and his love, the humans and the doves, this world and the next are indistinguishable, virtually identical.3 The simple declarative statements “I have lost my turtle-dove” and “I want to go after her” lose the linear elapse of cause and effect, coming to seem simultaneous, interchangeable, mirrored. Philip K. Jason asserts that “the villanelle is often used, and properly used, to deal with one or another degree of obsession” (140) and while this statement applies far less to villanelles circa 1900 than it does to villanelles circa 1950 and 2000, it is certainly true that the first villanelle can be read as obsessive.4 There is no visible logic such as “I have lost my turtledove, therefore I want to go after her” in the poem, because that would imply, however slightly, the possibility of another consequence besides the one the speaker is fixed upon. The “if” of the phrase “Si ton Amour est fidelle” (“If your love is faithful”) is not a real “if,” suggesting contingency and ambiguity and multiple possibilities, because the turtledove is already an emblem of unswerving fidelity. The very notion that a turtledove could be unfaithful is counterintuitive (akin to the notion of a nightingale with a sour voice); the “if” carries more the sense of a “since” or an “as,” serving to emphasize the resemblance between the lover and the turtledove. Both are equally faithful to their faithful mates, and therefore either the mourning lover or the mourning dove could speak the refrains. Their two laments are one.

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 As though learning the trick of “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle,” many contemporary villanelles have used the double-refrain villanelle to depict stark and inexorable psychological pathologies: Rita Dove’s “Parsley”; Edward Hirsch’s “Ocean of Grass”; Donald Justice’s “In Memory of the Unknown Poet Robert Boardman Vaughan”; Derek Mahon’s “Antarctica”; Marilyn Waniek’s “Daughters, 1900”; Michael Ryan’s “Milk the Mouse”; Tom Disch’s “The Rapist’s Villanelle”; Sylvia Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song.” And as though it were the best illustration of a tragic state of mind, Reetika Vazirani’s villanelle “It’s Me, I’m Not Here” was the only poem quoted in full in a Washington Post Magazine story concerning how the poet came to kill herself and her two-year-old son Jehan (19). Yet “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” can also be read as sentimental, conventional; the inconsequential “society” villanelles of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century are equally legitimate descendants of the turtledove. The trope of the grieving lover fixed on following his dead amour to the grave is merely conventional in the context of sixteenth-century Petrarchanism. In some ways “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” is more effective when read out of the context of its royal sequence (and it has virtually always been read out of context when it has been read at all in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries), since this renders its deferential conservativism less visible. Strand and Boland’s small slip in speaking of “his” (i.e., Passerat’s) “lost turtledove” reflects the fact that critics have been unaware that the poem was part of a sequence written for a royal patron.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 And indeed the poem is more respectable by modern standards if it is imagined to be in the voice of a romantic self attempting to express a deeply-felt internal psychological drama. Few poems in Passerat’s vernacular oeuvre could sustain such an interpretation, as even the nineteenth-century revivers of Passerat recognized. Passerat’s editor Blanchemain, who was familiar with all Passerat’s vernacular lyrics, opines that “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” “se trouve comme égarée au milieu d’élégies quasi-officielles” (“turns up like a stray in the middle of quasi-official elegies”) (vii); while Joseph Boulmier, a fervent admirer of “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” but not of Passerat’s other poetry, calls it a “naïf chef-d’oeuvre échappée, Dieu sait comme, à la plume du savant Passerat” (“naïve masterpiece escaped, God knows how, from the pen of the scholar Passerat”) (7). But when Blanchemain and Boulmier wrote those assessments (in 1880 and 1878, respectively), Passerat’s “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” had already been mistakenly hailed as the best example of a schematic type, and new poems in the same form had already been written. I would argue that “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” only looks exceptional in hindsight; we necessarily see it differently because of the poems that have come after it. Neither reading–the “obsessive” and the “conventional”–is more authoritative than another; the poem wears both aspects comfortably. Wink an eye, it moves one way; wink the other, it moves the other way.

- Tilley II.57; Kane 128; and Sainte-Beuve 121.

- Further research by a Renaissance scholar certainly seems indicated; I would certainly like to know whether the practice of deliberately varying spelling for poetic effect was a common one in the early modern period. Perhaps Renaissance scholars have already explored this phenomenon extensively; I don’t know. In the context of distinguishing between the oral-formulaic, improvisatory, mnemonic song tradition and the new text-centered madrigal of the Renaissance, Kane comments on the sixteenth-century phenomenon of “eye music,” in which “features of the musical composition […] were apparent to the eyes of the singer reading the score, but not necessarily to his or her ears. Words such as “day” or “light,” for example, would be set to white notes (half, whole, and double whole notes, called minims, semibreves, and breves), while “darkness,” “blindness,” “night,” “death,” and “color” required black notes (quarter notes, called semiminims)” (How 53). As Kane notes, such a practice foreshadows George Herbert’s experiments with visual poetic effects in the seventeenth century. Such examples show that, as seems natural, the increasing textuality of art in the sixteenth century led to artistic experiments with that textuality. Still, Passerat’s homographia, while well worth preserving, does not seem boldly experimental in the same degree: it strikes me as produced by the same kind of tidying urge that produced the convention of capitalizing the first letter of every line of a poem regardless of its sentence structure. It is a purely visual, textual phenomenon, and as such can be taken as a comment on the visuality of texts–but in some cases that comment is only half-realized: it just looks better that way.

- It is worth noting here that the many sonnets in the Tombeau de Fleurie pour Niré are all on the same rhyme scheme, abbaabba ccdeed, which lends weight to Kane’s point that Passerat was not particularly inclined to make formal innovations. The only mildly innovative feature of “J’ay perdu ma Tourterelle” is that it has two distinct refrains instead of one.

- In another chapter I discuss the imposition of meaning on poetic form in more detail; too often, critics seem to extrapolate the axiom that villanelles are intrinsically obsessive from the undeniably accurate observation that contemporary villanelles often deal with obsession. Such axioms are historically constructed, I argue; for now it suffices to point out that Victorian and Edwardian accepted wisdom held that the villanelle was suited only to light subjects.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24

0 Comments on paragraph 25

Leave a comment on paragraph 25

0 Comments on paragraph 26

Leave a comment on paragraph 26